Defining Good Translation: Japanese have great interest in quality control theories, including the Deming theory, the QC cycle, the 5S method, Total Quality Control (TQC) and Kaizen. I believe the common theme running through these theories is thoroughness, attention to detail, or in the words of Benjamin Franklin, care. In translating, care can be applied from a general and a specific perspective. General care focuses on accurate representation of the meaning and tone of the original, and use of a clear and appropriate style and tone which is suitable for the intended audience. Specific care focuses on details including not just correct grammar, spelling and punctuation but choosing words and expressions which most accurately represent the meaning of the original in the minds of the target audience. As Franklin noted, someone may have great learning and talent, but unless he applies those abilities with care, the resulting work can be lower in quality than the work performed by a less experienced person who uses care. Thus, the best translation results when a translator with strong language skills and specialized background knowledge applies his skills with care. Care, however, is born of an attitude toward one's work. It is based on the knowledge that one can always go on learning and improving one's skills. It has been said that there are four stages of competence, namely unconscious incompetence, conscious incompetence, conscious competence, and unconscious competence. However, I believe anyone who applies care intentionally refrains from proceeding to the fourth stage but always applies his skills consciously.

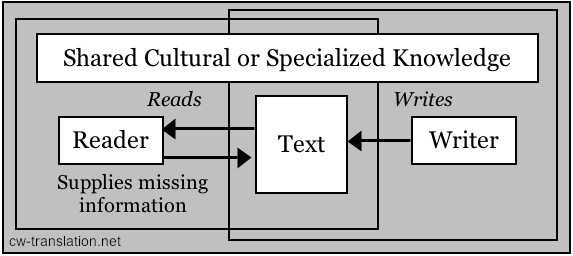

The Meaning of Accuracy: As noted in the Quality Control page, translation is a kind of adapter which accurately converts the ideas and feelings of a written text from one language and cultural context to another. The meaning of accuracy, however, is not as simple as it may seem at first sight. To understand what accuracy really means, we have to take a closer look at the nature of translation itself. The Japanese writer, translator and educator Tsuneo Yatagai highlighted the importance of commonly shared cultural knowledge between writers and readers using a figure similar to the one at the right. The figure shows that an author or speaker will omit, most often unconsciously, any information he assumes his readers already know. This tendency to omit all but the essential is particularly strong in Japanese, as noted by Yurika Sanmori of the Tsukuba Language Arts Institute.

The Meaning of Accuracy: As noted in the Quality Control page, translation is a kind of adapter which accurately converts the ideas and feelings of a written text from one language and cultural context to another. The meaning of accuracy, however, is not as simple as it may seem at first sight. To understand what accuracy really means, we have to take a closer look at the nature of translation itself. The Japanese writer, translator and educator Tsuneo Yatagai highlighted the importance of commonly shared cultural knowledge between writers and readers using a figure similar to the one at the right. The figure shows that an author or speaker will omit, most often unconsciously, any information he assumes his readers already know. This tendency to omit all but the essential is particularly strong in Japanese, as noted by Yurika Sanmori of the Tsukuba Language Arts Institute.

Closeness, Flexibility and Suitability to Purpose: Unlike English, there are few rules governing sentence structure in Japanese, and it is considered exceedingly tedious and unnatural to both writer and reader to explicitly state the subject in each and every sentence. Differences in what might be called the topography of definitions is another way in which cultural knowledge differs. The Japanese-English translator must understand the whole of that cultural knowledge which the Japanese audience possesses. If he believes the English speaking audience does not share that knowledge, he must sometimes provide it in some way depending on the intent of the author and the importance of accuracy versus closeness as determined by the reason for the translation. As noted already, expository prose communicates concepts while literary prose communicates feelings or sentiments. Thus, cultural "knowledge" is both conceptual and emotive. Some kinds of texts, such as magazine articles meant to entertain, tend toward the emotive and are therefore stress the literary. Other types of text, such as statutes and contracts, are more expository than literary. For this reason, they often require very close translation. Expository prose lends itself to a more literal translation. But it would be misguided to adopt this same literal approach to translating a prose which is more literary in character, such as a magazine article, because it naturally expresses idiomatically and culturally unique features of a language. The translator must therefore translate these unique features into correspondingly unique features in the target language based on his understanding of both languages and cultures. In this way, the definition of faithfulness in translation differs according to the nature of the text. The translator must have a keen sense of judgment in order to decide where to find the optimum balance along the continuum between closeness and flexibility. Thus, the translator must work in several dimensions. He must stress accuracy regarding the intended conceptual communication in so far as a text is expository and relatively free of emotive communication. In other words, cultural knowledge is both conceptual and emotive, and the translator must take care to convey both in just the right combination, based on the intent of the author and the intended purpose of the translation.

My Approach: In implementing a philosophy of care on the general level, I follow the advice of Professor Peter Newmark, formerly Dean of the School of Languages of the Polytechnic of Central London. In his book, Approaches to Translation (Oxford: Pergamon Press, 1981, p.6), he observes that, "A translator must respect good writing scrupulously by accounting for its language, structures and content, whether the piece is scientific or poetic, philosophical or fictional. If the writing is poor, it is normally his duty to improve it...." In so far as the main purpose of expository prose is the communication of ideas, it should be clear and plain. Indeed, clarity is one of the hallmarks of intelligence and logical thinking. It is also a sign of intellectual honesty. As Professor Newmark notes, a translator is bound to translate the source text into the best possible English. On the specific level, the following examples may serve to illustrate my approach to care, cultural knowledge accuracy. The first concerns problems which can arise with the use of the expression "fiscal year." The second focuses on problems related to the use of the term "Japanese government bonds," or "JGBs."

Example 1. Fiscal Year Versus Nendo: If someone were to hand you a set of financial statements and tell you they are the financial statements of XYZ Corporation for fiscal year 2013, and if you knew that the balance sheet date of XYZ Corporation was 31 March, what 365-day period would you assume the statements cover? The answer to this question is not as easy as you might think. For if XYZ Corporation were a Japanese company rather than a North American or British company, you could not know for sure until you found an expression reading, "Balance Sheet of XYZ Corporation for the Year Ended 31 March, 201-." About a quarter of the companies in the S&P 500 use a fiscal year system rather than a calendar year system for their financial or accounting year. This means that their financial years begin in one calendar year and end in the next. The universal practice in the West, moreover, is to designate the fiscal year by the calendar year in which it ends, not the year in which it begins. For example, Cisco Systems Inc. ends its financial year on 27 July and McKessson Corporation ends its fiscal year on 31 March. In both cases, the companies designate their fiscal year using the calendar year in which their 365-day accounting period ends. The U.S. Senate also defines the government's fiscal year as 1 October through 30 September of the following year and specifically notes that, "The fiscal year is designated by the calendar year in which it ends; for example, fiscal year 2013 begins on October 1, 2012 and ends on September 30, 2013." In Western accounting and business practice, the expression "fiscal year 2013" is used interchangeably with "the fiscal year ended 2013." This is not however, the practice used in Japan, at least when using the expression nendo. As noted below, there is more than one way for a business firm to designate its fiscal year in its financial statements or other financial documents. But when using the term nendo, the calendar year in which the 365-day period begins is used to designate the fiscal year. In my early years as a translator in the 1980s, I was surprised to find that most Japanese companies would translate "1986年度" (1986-nendo), for example, straightforwardly as "fiscal year 1986," apparently unaware that Westerners reading the financial statements will assume that the statements referred to the year ended 1986 rather than the year ended 1987. As the years have gone by, I've noted that Japanese corporations have clearly become aware of the problem. Most Japanese financial statements now specify the starting and ending dates of the relevant fiscal year, or use the standard expression, "for the year ended...."

Thus if given a set of financial statements to translate, the translator must first understand that nendo can not be blindly rendered as "fiscal year," at least if the same calendar year is used in the Japanese and English versions. If the same year is used, the translator must append some parenthetical comment such as, "fiscal year 2013 (ended 31 March 2014)" or otherwise clarify for readers which 365-day period is being referred to. Personally, however, I do not recommend this. Translated documents should be prepared in a form and style which the intended audience is used to. This is why many Japanese companies and financial institutions are translating the Japanese "2014年度" (2014-nendo) as "FY2015," using the year in which the 365-day financial year ends. As noted previously, words are symbols. This problem illustrates that a word-symbol from one culture may appear to correspond exactly with a given word-symbol in another language but actually differ in important ways. In short, the numerical component of the Japanese symbol/concept "2014年度" must be "translated" into the Western symbol-concept "FY2015" owing to the different meaning of the literal component. Unless this is done, the translation can not be considered accurate, and that inaccuracy could have disastrous results. (When corresponding to a calendar year from January through December, the letters FY may conveniently be read as financial year rather than fiscal year.) The translator can not do good work merely by looking up word-symbols in a dictionary. The translator's job is to gain a full and complete understanding of the concept represented by the symbol and then search for a word-symbol in the target language which corresponds precisely to that same concept in every context. But the exact concept may very well not even not exist in the target language. If not, then there will be no word-symbol representing it. The translator might then choose a similar word-symbol in the target language because it represents the concept adequately for the purpose of the present context. However, this course of action can be risky. If the relevant word is a neutral, commonly used word, few problems arise. But if the word is a specialized term, the reader might be led to think that the correspondence exists in other contexts as well. This will give rise to problems over the long term by creating a bad precedent. Simply choosing "fiscal year" to translate nendo in this case can be perilous because an investor or other stakeholder may want to compare a business firm's financial statements in two consecutive years. If he uses the wrong two years, the results could be very damaging. The same is true if the stakeholder is reading a financial report written by an organization which is relying on the skills and accuracy of the translator. Thus if the translator does not do his job well, he could cause damage for the client which is relying on his services. The translator must therefore use his inventiveness in some way to ensure that the target audience understands the original concept. He may do this by inventing or coining a word, as "pioneer" translators have done through the ages. Or he may use the closest word but add a clarifying note, as suggested above in this example. On the other hand, he might decide simply to use the word as it stands in the source language while adding a short, parenthetical explanation. Indeed, this sort of situation is one of the ways in which words in one language migrate into and become a part of another language. In any case, the translator must anticipate potential misunderstanding and ensure than the target audience accurately understands the concept which the writer is trying to communicate. A translator's job is to communicate concepts and feelings, not merely to blindly transcribe symbols. This situation is also a good example of the kind of problem that the translator should call the client's attention to. The translator can then suggest what he believes is the best solution to the problem and then follow the client's preference from that time forward. There is, however, a happy epilogue to this story.

An Alternative Solution: Actually, there are two Japanese methods for referring to a fiscal year and the second doesn't give rise to any problems when translated into English. Over the years, I've noticed that more and more Japanese companies seem to be abandoning use (for example) of 2013-nendo (2013年度) in favor of the more precise expression 2013-nen-sangatsu-ki (2013年3月期), which means "the year ended March, 2013." The expression 2013-nen sangatsu-ki (2013年3月期) refers to precisely the same 365-day period as 2012-nendo (2012年度) except that the period is identified using the calendar year in which the last month (and hence last day) of the fiscal year falls. I therefore make it a practice to encourage Japanese writers to avoid using nendo and instead use the -sangatsu-ki form because the designation of the year will then be the same in both the Japanese and the English financial statements, thus averting possible confusion. In any case, use of an expression such as "for the year ended" avoids ambiguity. Some Japanese companies have adopted a practice popular among many British and Commonwealth companies of using a dash ("2013-2014 fiscal year") or, as is apparently more popular on the Continent, a slash ("fiscal year 2013/2014").

Example 2. Kokusai (国債), JGBs and JGSs: The second example of my approach to care relates to the translation of the Japanese word Kokusai (国債), or Japanese Government Securities (JGSs). Decades ago, before the Bank of Japan began using "Japanese Government Securities" (JGS) for Kokusai, an unfortunate precedent was set under which the word was almost universally translated as "Japanese Government Bonds" (JGBs). To fully appreciate why this is incorrect, however, it is helpful to review the fundamental difference between short-term and long-term debt securities issued by governments. (References are given at the foot of the page.)

Bonds and Bills, Capital Markets and Money Markets: A bond is a contract in which the bond issuer (borrower) agrees to pay the bondholder (the lender) a stream of money (Pindyck 538). The borrower contracts to pay the lender a fixed sum of money at regular, predetermined intervals (the coupon payments) until a certain date on which the borrower repays the face value (principal), thus repaying its obligation (Pearce 42, 272). Bonds are considered "long-term" debt instruments because they mature in more than one year. The two defining features of bonds to be remembered for our purposes, then, is that they represent a debt in which interest is paid at fixed intervals and they mature in more than one year. Together with stocks, bonds form a part of the capital markets. The capital market is a market for financial instruments, including fixed-income and equity securities, having maturities greater than one year. (Choudhry 256, Jones 27). From the accounting point of view, bonds represent a part of the issuer's debt capital. In contrast, bills (including Treasury Bills or Treasury Discount Bills) are debt instruments which are issued at a discount and redeemed at face value. They are bought and sold in the money market. "Money market" is an umbrella term that includes markets for bank accounts, term CDs, interbank loans, money market mutual funds, commercial paper, Treasury Bills and other instruments. They are money markets because maturities do not exceed one year and the assets are easily convertible into cash. (IMF) U.S. Treasury Bills are the most important short-term securities in the international financial markets (Questa 20). Bills and bonds therefore differ in two fundamental ways, (i) whether they pay interest through discounting or periodic interest payments and (ii) whether their maturity is no more than one year or more than one year. Needless to say, Japan, Britain and the United States each issue bonds and bills. Keeping in mind the basic difference between short-term and long-term debt securities, let us take a close look at the bills and bonds issued by the three countries with special attention to how each type of instrument is and should be translated.

United States Treasury Securities: The following table summarizes the debt securities issued by the United States government and indicates Japanese translations for each.

The first point to note regarding the nomenclature used to refer to U.S. Treasuries is that the different maturities are referred to by three unique designations, namely bills, notes and bonds. Some caution is needed, however. The U.S. government applies the designation "Treasury Bonds" to U.S. government debt securities having maturities exceeding ten years (currently only the 30-year Treasury Bond). On the other hand, Treasury Notes are indeed "bonds" if we consider the meaning of the word "bond" as defined above. There is no unique term to refer to U.S government capital-market debt securities, namely Treasury Notes and Treasury Bonds but excluding Treasury Bills, which are traded in the money (or "discount") market. This is probably the reason that many financial writers refer ambiguously to "Treasury bonds" (with a small "b") to refer to capital-market government debt securities, namely Treasury Notes and Bonds. Britain and Japan do have such terms, though ironically Britain has no specific term referring to all government debt securities. As we shall see below, only the Japanese, it seems, have overcome this ambiguity and have terms to refer specifically to either money-market or capital-market government debt securities, or both together.

U.K. Gilt-Edge Securities (Gilts): The following table summarizes the debt securities issued by the British government and gives Japanese translations for each.

Gilts are British government debt securities issued by the British Treasury with initial maturities of over 365 days. (Choudhry 261). In other words, Gilts are by definition capital-market debt maturing in over one year. In contrast with the American nomenclature regarding Treasuries, Gilts do not include money-market government debt securities, namely Treasury Bills. As noted above, however, there is no specific British term to refer to government debt securities of all maturities. I am advised by the Debt Management Office that one must use an expression such as "Gilts and Treasury Bills," or "UK marketable securities" or "UK debt securities."

Japanese Government Securities (JGS): The following table summarizes the debt securities issued by the Japanese government and gives English translations for each.

The Bank of Japan Accounts designates kokusai (国債) as "Japanese Government Securities (JGS) in English and defines them as "Japanese Government Bonds + Treasury Discount Bills." Indeed, in Japanese, the term kokusai encompasses all Japanese government debt securities, both short-term (money market) and medium- and long-term (capital market) debt securities. It therefore corresponds to the American term "Treasury Securities," while "Japanese Government Bonds" (JGBs) corresponds to the British term "Gilts." Accordingly, the correct translation of kokusai is "Japanese Government Securities," not "Japanese Government Bonds."

As noted elsewhere on this website, words are symbols representing concepts, and translation proceeds from concept to symbol in the source language to the corresponding concept and symbol in the target language. The first task of the translator, then, is to clearly understand the concept and its relationship to the symbol(s) representing it. This task begins with identifying the definition of the concept, including its "topography," or the way in which its various attributes link it to the other closely related concepts which together comprise the schema in which it is embedded.

------------------------------

References: